A leaked letter from Kenya’s auditor-office general’s in December 2018 fuelled speculation that Kenya had staked its thriving Mombasa Port as collateral for the Chinese-backed Standard Gauge Railway. Our latest research demonstrates why the collateral rumor is false.

Edward Ouko, the former auditor-general, was wrapping up the national ports authority’s 2017/18 audit. He cautioned that if Kenya defaulted on the US$3.6 billion railway loans, China Eximbank might seize the port authority’s assets, the most important of which is Mombasa Port.

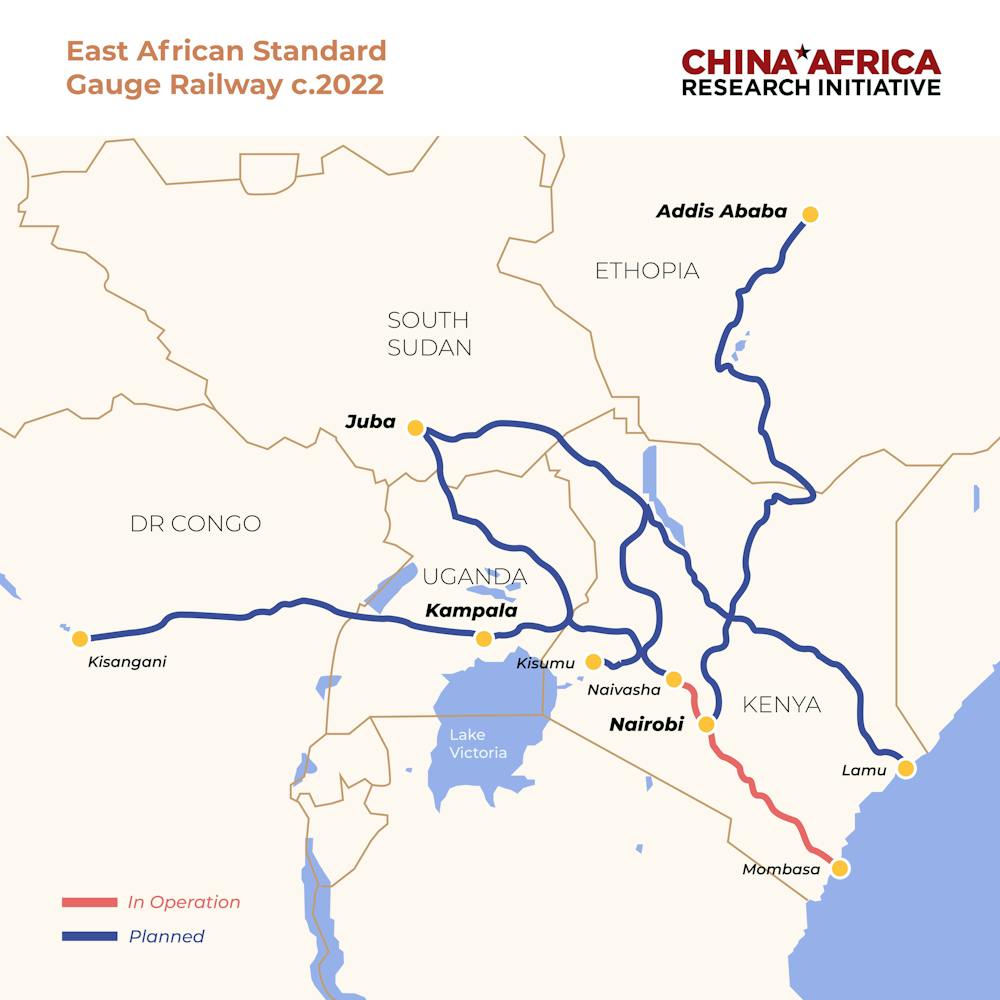

East Africa’s principal international commerce gateway is the profitable Mombasa Port. The railway, which opened in 2017, was designed to connect the port to Nairobi, Kenya’s capital, and other landlocked countries beyond.

Kenyan suspicions echoed a widely publicized story from earlier this year. When Sri Lanka had problems repaying Chinese loans, China was alleged to have “seized” Hambantota Port, according to the narrative. The “debt trap diplomacy” claim was later debunked, but not before it generated concerns about other major Chinese initiatives.

Both the Chinese and Kenyan governments denied Mombasa Port was collateral, but neither provided an explanation. Our team of international commercial law and project finance professors and practitioners spent months collecting original documents and analyzing the project’s contractual framework, perplexed by the leaked letter.

We were surprised to learn that the rumor was sparked by the auditor-seemingly general’s minor but important misreading. The auditor general

Kenya’s government had “expressly guaranteed” that the ports authority’s assets could be utilized to repay the Chinese loan due to sovereign immunity. Both charges made by the auditor-general were false.

Technical terms and procedures complicated the dispute over the railway and Mombasa Port for the auditor-general and many others. These terms are commonly used in international project finance law and business, although they are unfamiliar outside of this context.

Although some public education would have been required, the release of the contracts (which Kenya’s High Court ordered the government to publish just last week) could have prevented the auditor-error general’s and permitted debate based on facts rather than rumors.

Creating a project map

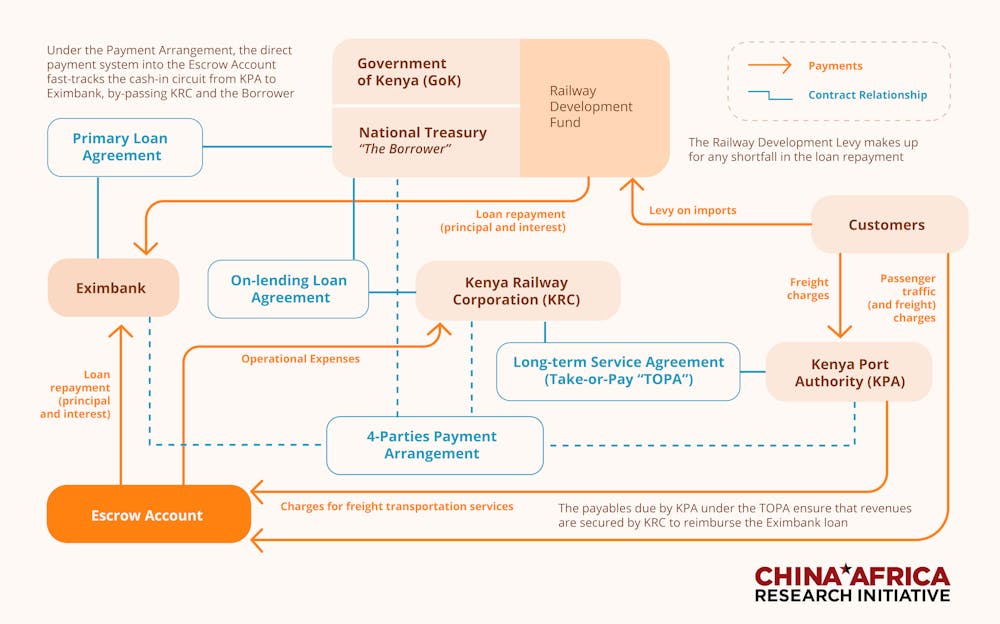

Kenya’s National Treasury (borrower), Kenya Railway Corporation (project firm), Kenya Ports Authority, and China Eximbank were the four major players in the Standard Gauge Railway funding (the lender). The intricate contractual and payment agreements are depicted in the diagram below.

In a 2013 briefing to Kenya’s parliament, Kenya’s Treasury detailed the railway’s financing arrangements and credit upgrades. The government had negotiated for many credit upgrades to increase the project’s financial viability and make it “bankable.”

A “take or pay” arrangement between the national railway corporation and the ports authority was one of them. The ports authority agreed to ship (or “accept”) a minimum volume of cargo on the new railway per year under this 15-year arrangement. Kenya Ports Authority would use its own income to compensate (pay) the shortfall if cargo shipments fell below the agreed-upon annual amount.

The ports authority is thus the main client of the Standard Gauge Railway, not its collateral. The treasury also promised to assist the project with the railway development fee, a 1.5 percent tax on Kenyan imports.

The blunders

One of our most critical conclusions is that the government’s chief auditor referred to Kenya Ports Authority as a borrower incorrectly. If the ports authority had been a borrower, it would have co-signed the Chinese loans and shared responsibility for repayment. However, the port authority is not a borrower in any way.

“Each of the Borrower, Kenya Rail Company, and Kenya Port Authority agrees…”, according to clause 17.5 of the four-party agreement cited by the auditor-general in its report.

This pertains to three entities, according to our legal expert: Kenya’s Treasury (the borrower), the rail operator, and the port authorities.

Despite this, the auditor-general misinterpreted the language, supposing it to refer to two entities: “each of the debtors, in this case Kenya Railways Corporation and Kenya Ports Authority…”

The auditor-general then cited Clause 17.5 as evidence that the ports authority was a borrower, putting its assets at risk. The ports authority was accused by the auditor of failing to report this during the audit. The auditor-assessment general’s on the ports authority’s responsibility was affected by faulty assumptions.

What does it mean to waive sovereign immunity?

“Waivers of sovereign immunity” were signed by the Treasury, Kenya Ports Authority, and Kenya Railways Corporation. Because they were all parties to various contracts in the entire bundle, this is the case. Sovereign states and the institutions they control enjoy sovereign immunity under international law. This implies they are largely immune from lawsuits and cannot be forced to appear before a foreign court or arbitrator, or to enforce a judgment rendered outside of their boundaries. However, few international banks will make a loan if there is no chance of arbitration in the event of a disagreement and no legal recourse if the borrower defaults.

A cache of loan agreements signed by Cameroon with banks and export credit agencies in Austria, India, Germany, Spain, Turkey, and the United States has been made public.

It would be professional negligence to leave a sovereign immunity waiver out of an international commercial loan deal.

However, there is a significant difference between a general sovereign immunity waiver and identifying a specific asset as collateral, such as a port.

Our findings debunk similar rumors that borrowing governments had pledged critical assets such as land or ports in exchange for Chinese funding. Zambia (Kenneth Kaunda Airport), Uganda (Entebbe Airport), and Montenegro are among them (Port of Bar).

The debt trap diplomacy worry that Chinese banks are directly (and deliberately) putting borrowers’ strategic assets at danger continues to fail the proof test.